Will Google's New AI Tool Help Teachers?

"Learn Your Way" Shows Promise but Has a Way to Go

I’ve complained that the problems AI poses for teachers are immediately apparent, but the advantages have been promises deferred. We now have a peek at one tool a major player—Google—is working on.

This education product seems to play to one the current crop of LLM’s core strengths—writing text. “Learn Your Way” is designed to rewrite textual educational content to tune the material to individual students. The published information makes it seem like it’s off to a stuttering start, but I think the idea has real promise.

The goals is that the user can upload material (such as a textbook PDF) and the system can perform the following changes

1. Rewrite it to match the user’s specified grade level

2. Rewrite it to match the user’s personal interests

3. Generate the material in multiple formats, including interactive text, narrated audio lessons, mind maps, and adaptive quizzes.

There has been one not-very-good pilot study of efficacy (more on that below) so we are mostly left to speculate about the likely usefulness of these features, and speculate as to how well Learn Your Way implements them.

Simplify: Can LLMs simplify texts while retaining meaning? It’s a capability already available on most or all of the LLM chatbots, but empirical data on how effectively they do so are sparse. Two things seem predictable. Current performance will be uneven, and performance will improve with new models.

On the one hand, making this feature easy to access may pay off. I expect there may be times that a teacher wants students to access a topic via a text and cannot find one that is not beyond the reading capabilities of most students. And it could help struggling readers and second language learners access academic content that would pass them by.

On the other hand, this feature must be used judiciously, of course. Tim Shanahan has written persuasively about the need for students to grapple with texts they find challenging and also evidence showing that too many teachers given in to the temptation to assign texts that can be read without much difficulty, instead of encouraging students to work through the problem and teaching them strategies to do so.

Alternative representations: Translating ideas into different representations is foundational to instruction; teachers are always thinking about what students should experience to make an idea click: should they hear an explanation, see a figure, execute an activity? Alternative representations certainly can help, but they can also distract and they require instruction; students must be shown how to connect one representation with the other, especially when they are novices. It’s not clear to me whether Learn Your Way will discriminate between content that would benefit from a graphic representation, a mind map, a figure, and so on, or just provide alternatives upon request. The website provides all.

(The mind maps I saw needed work. Every one used a hierarchical representation and was more like a standard set of notes than map.)

Personalization: Perhaps the most interesting feature is the ability to tune the content to a topic that interests the student. If a middle schooler is to learn about, say, the immune system, and the student is passionate about gaming, you can tell Learn Your Way to rewrite the text to incorporate the student’s interest.

Every teacher has tried to pique student’s interests by connecting to-be-learned content to topics that already interest the student; make your math problems about Taylor Swift, and students will eagerly simplify those equations! One problem in implementing that strategy is that some of your students love Taylor Swift whereas others can’t stand her. (And for some, it’s a painful subject since the release of Life of a Showgirl.) Learn Your Way solves that problem—each student can choose their own topic.

But even for students who love her, inserting Taylor Swift’s name into a standard word problem about buying watermelons is not enough to make students interested in the underlying math. Maladroitly done, the real meaning of Taylor Swift to the student is not made intrinsic to the new math material. She is mere window dressing.

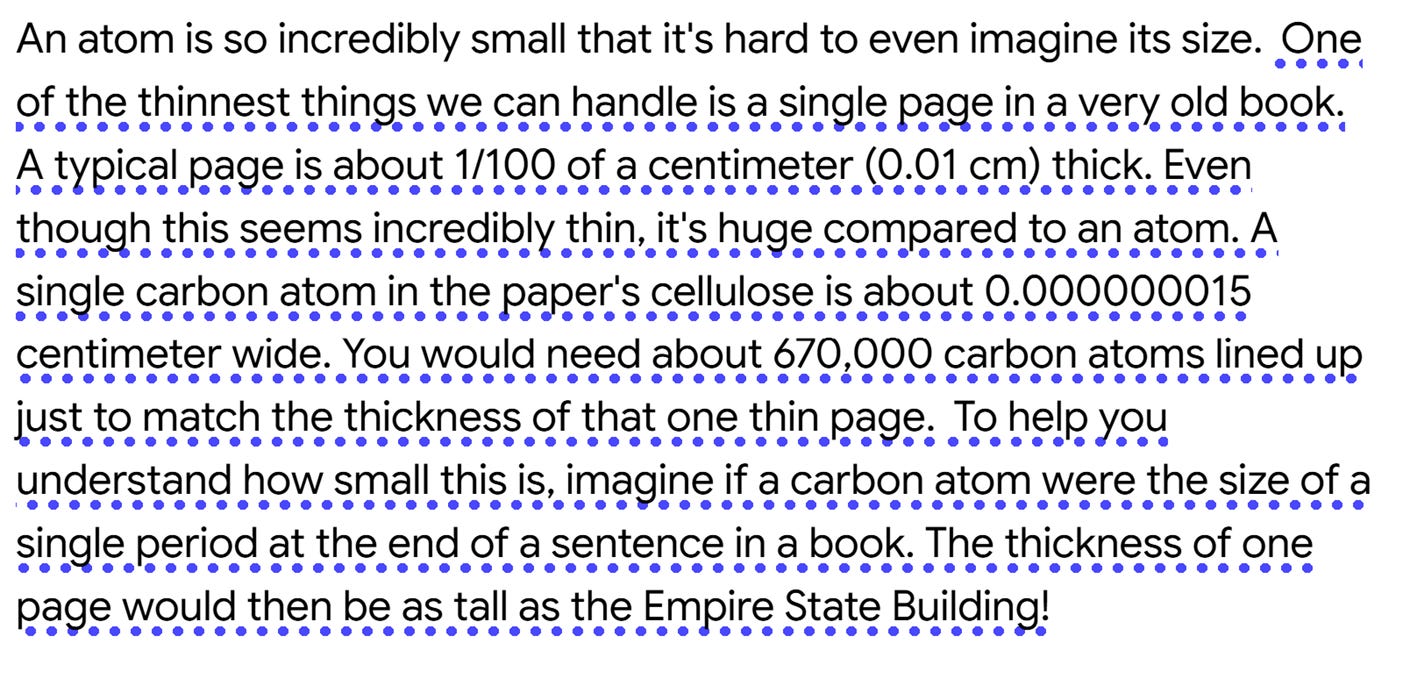

Learn Your Way does not seem to solve this aspect of the problem. Consider this example of a text on “atoms and molecules” for a middle-schooler who likes books.

The original text used compared the size of atom to a spider’s web, and the Learn Your Way has changed it to the page of a book. A middle schooler who says he “loves books” didn’t say he loves books because he loves bindings and glue, and he doesn’t marvel at the slender grace of pages. He loves the excitement of learning new things, and/or the feeling of getting lost in a narrative. Learn Your Way’s example highlights an irrelevant property.

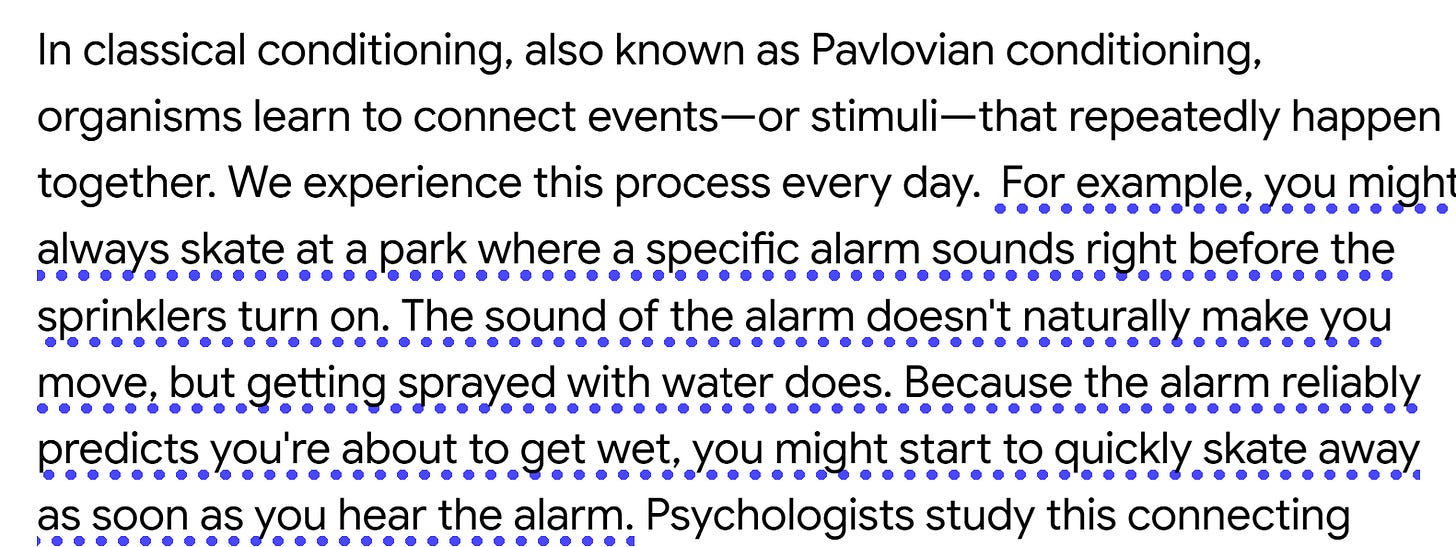

Or consider this example from the website, which offers a text to teach principles of learning to a high school student who loves skateboarding.

This example is not going to spark recognition in a student—“totally! That’s what skating is like, there’s an alarm and then you get wet!” Skating in this example is window dressing. (Worse, the example is inaccurate. This is operant conditioning, not classical conditioning.)

I wanted to try Learn Your Way on my own examples, but I can’t access it. So I asked Gemini, which I recognize is not really fair—it’s not trained for this specific function. But let’s hope that Learn Your Way is better than Gemini. I asked for about 10 examples of classical conditioning in a number of domains, and always got similarly surface-level connections between the concept and the domain. For example, when I asked for an explanation of classical conditioning that would interest a gemstone collector, the CR was a the click of a jewel case, and the US was the joy of seeing a gem. (Also strange—Gemini always provided examples of emotional conditioning.)

Still, I think the idea of having an LLM rewrite a text has promise. As we’ve all heard a million times, you get better results if you give better prompts. Learn Your Way may not be able to extract deep structure in a way that allows it to map an example to a novel domain, so you end up with a shallow example. If the user specified the deep structure, it would probably do better.

If Learn Your Way cannot be modified to appreciate deep structure and come up with better examples and analogies, it could still be useful if authors wrote skeletal texts with clear specifications of deep structure which Learn Your Way would then flesh out with examples and analogies from domains that individual users specified.

That scenario would solve another potential problem—copyright. Currently Learn Your Way allows you to upload a pdf for change. The website pretends that we’re all going to limit ourselves to open source materials. I’m no lawyer, but I wonder whether Google might not be liable for making copyright violation so easy. (Candidly, I hope so.)

Learn Your Way strikes me as in need of significant development, but a potentially useful classroom tool for teachers.

The not-very-good pilot:

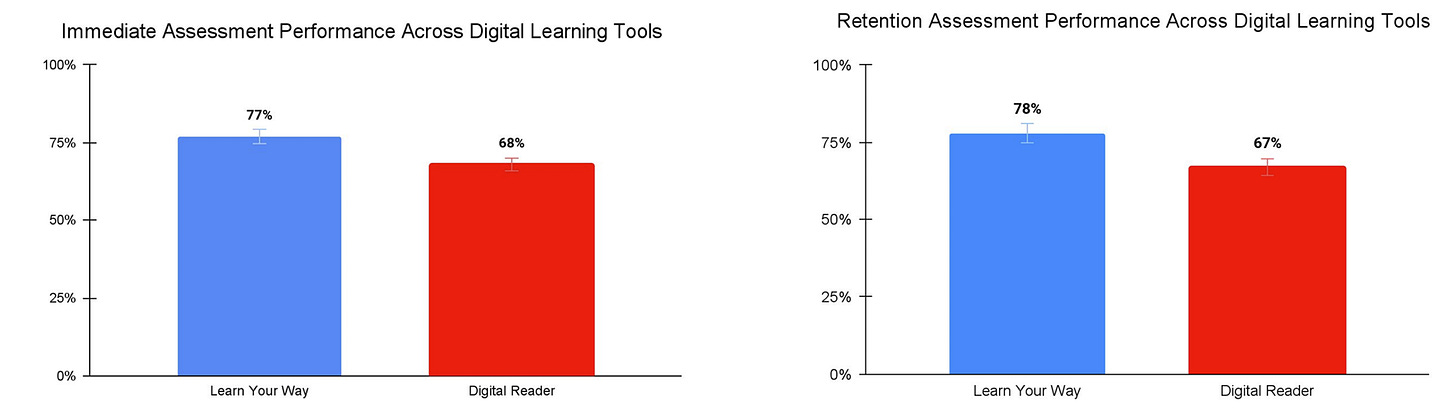

Google reports a pilot study of sixty high school students—so we have just 30 students in each group. They were given an open source chapter on brain development, either the original or transformed by Learn Your Way. A content expert generated a test to be given immediately after reading. Another was emailed to students three days later, and students had had four days to complete it. (Which seems like it introduces a lot of variability in the delay, and the experimenters did not report data regarding when participants in each group submitted the test). Subjects were to take between 20 and 40 minutes reading and studying the chapter. (Study time data for the two groups also not reported.)

There was a modest but reliable difference in test outcomes.

You can try Learn Your Way here, but note that there is a waitlist, and you must be approved. I applied but had heard nothing after four days.

Very interesting, Daniel. Thank you for this.

I sense a few risks, however.

To begin, I think there ought to be a healthy skepticism about this kind of personalization. Claims of this kind latch on to underlying concerns about student engagement, which has ironically eroded under the influence of attention-capturing technologies like those brought to market by companies such as Google.

Second, the overuse of a tool like this, as justified by increased engagement, risks teaching youth that the only ideas worth entertaining are those that appear personally relevant to the individual. This narrows students’ horizon of curiosity, and thereby their learning potential.

Lastly, the social dynamics of a classroom, where students are asked to grapple with the SAME text, leads to something far more significant: negotiated understanding. This is crucial to the civic health of our societies.

Obviously, there could be a place for tools like this in education, but I fear that their effectiveness in engaging students may lead to the degradation of the important processes of learning that I outline above. And truthfully, it’s increasingly difficult to trust the technologies delivered by companies like Google, which have an imperative to capture attention and data for profit, even if that requires behavioural manipulation. We must remind ourselves that this is the ultimate mission for Google and their competitors: their bottom line.

But I greatly appreciate the hope in your piece. And I’m grateful that you brought this new product to my attention.

Your timing is great, though, because tomorrow, I’m publishing a new piece that performs a similar analysis of Alpha School, the new AI-powered private school, through the lens of McLuhan’s tetrad for anyone who might be interested.

I wrote this post about the personalisation aspect of Learn Your Way with Google - https://substack.com/home/post/p-175699748